[1200 Words; 4 Minute Read] Concern over climate change and a focus to improve and protect natural resources and improve ecological health have been promoted via the (environmental) sustainability agenda. Sustainability in simple terms is the capacity to endure. In more contemporary writing with regards to economics, ‘sustainability’ has been described as an economy in equilibrium with basic ecological support systems (Stivers, 1976).

Sustainability has since taken on greater meaning with regards to the environment and its connectivity to development. In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development provided a definition of sustainability that was included in its findings, which became known as the Brundtland Report (WCED, 1987). The report stated that sustainable development meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Defining what sustainable means is often a stumbling block for researchers and practitioners approaching this subject, although it may be more fruitful to consider the ‘spirit’ of the message – to maintain stability over a period of time. Confusions and clarity on sustainable concepts are recognised by Gilpin (2000) where he states:

‘Sustainability, like apple pie and motherhood, is everyone’s favourite. Business people are keen on sustainable profits, sustainable growth, and sustainable investments; academics may search for sustainable arguments; designers may seek sustainable performances. In the end, sustainability simply means keeping things going for a long period of time, perhaps indefinitely’ (Gilpin, 2000).

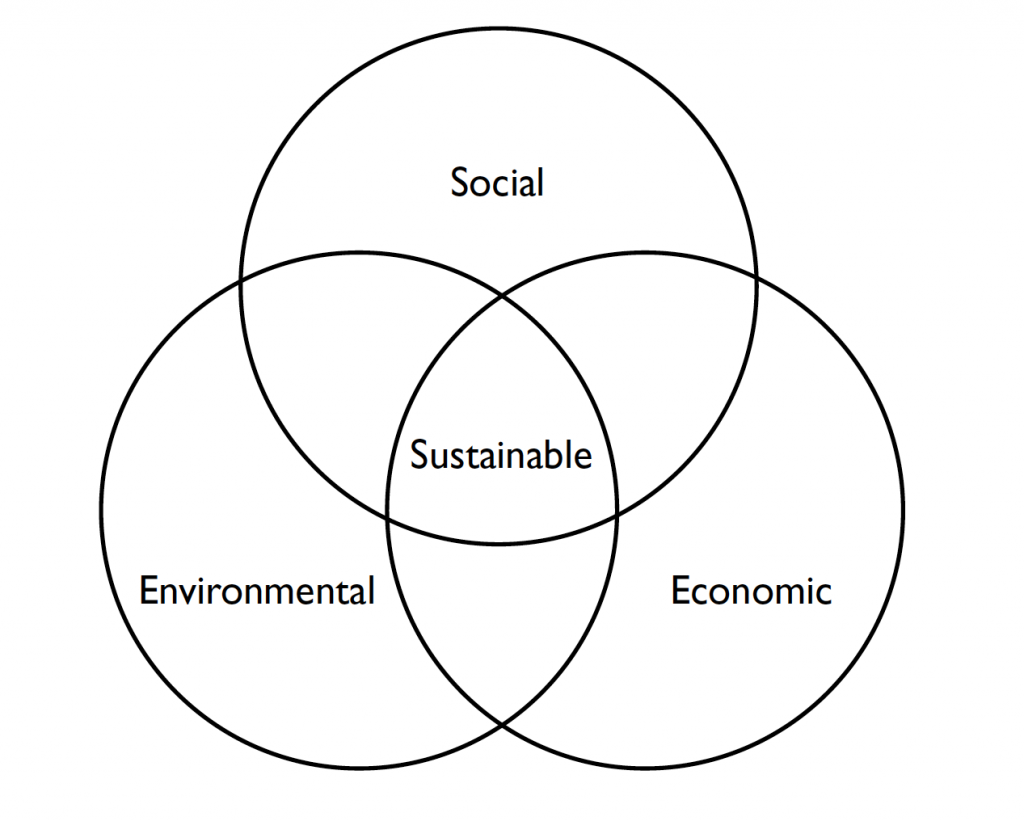

More recent conceptualisations build on the multiple ‘pillar’ approach. For instance, sustainability recognises that the three ‘pillars’ of the economy, society and the environment are interconnected rather than mutually exclusive (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Three Pillars of Sustainability

Further sustainability issues are that some phenomena are progressive for a moment in time, and will only for an instant provide some step change. The idea to sustain something is inextricably associated with time, so arguments can be brought out to whether sustainability is inherently conservative or progressive in approach. Sustainability could be seen as conservative in that it has desires that keep the status quo and remain the same. This raises questions as to whether society wishes to sustain obvious socio-economic inequalities – especially if the gap between rich and poor is sustainably widening. Furthermore, we could have sustainable inequality and an unfair system of resource allocation, or a loss of habitat continuing for a long period of time, or almost indefinitely.

This changing quality of person and place is where ‘the urban’ question and ‘development’ begin to intertwine with sustainability. Whilst appearing to be a noble aim in itself, sustainable development involves temporal variances of time that are either past, present, or future – as well as bringing various periods of time that are either short term or long-term. For future thinking, sustainability needs to be aware of how any development should encompass both short-term benefits as well as implications for longer-term success. We conclude here with two useful landmark sustainability quotes that tie sustainable development and urban development thinking:

‘Improving the quality of life in a city, including ecological, cultural, political, institutional, social and economic components without leaving a burden on the future generations. A burden which is the result of reduced natural capital and an excessive local debt…the flow principle, that is based on an equilibrium of material and energy and also financial input/output, plays a crucial role in all future decisions upon the development of urban areas’ (Urban21, 2000)

‘With over 70% of Europeans living in urban areas, cities and metropolitan areas are the motors of economic growth and home to most jobs. They play a key role as centres of innovation and the knowledge economy. At the same time, urban areas are the frontline in the battle for social cohesion and environmental sustainability. The development of disadvantaged urban areas is an important step in unleashing economic powers by creating more cohesive and attractive cities’ (EC, 2009)

A full and formated version of this article can be cited as:

Squires, G. (2013). Chapter 13: Policy and contemporary challenges. In Squires, G. (2013) ‘Urban and Environmental Economics. Routledge.