[3100 Words; Reading Time 24 Mins]

Ideas, concepts and theories are developed from intellectual thoughts that are of importance when studying urban and environmental economics. This article will provide initial thought on the origins of economic thinking that underpin its application to urban areas and environmental resource allocation. ‘Modern’ economic thought will be expressed from the writings of significant and pivotal thinkers such as Thomas Malthus on population, David Ricardo on trade and rent, and John Stuart Mill on limits to growth. As the economic discipline has progressed so too has its applied focus to urban and environmental issues, of focus here is the work developed further by Arthur Cecil Pigou on welfare economics and Ronald Coarse on behaviour.

- The Origins of Economic Thinking

The origins of economic thinking can be conceived to date back to when humans bartered for goods or exchanged through a system of gifts. From 9,000-6,000 B.C., livestock was often used as a unit of exchange as barter. Later, as agriculture developed, people used crops for barter. For example, a farmer could ask another farmer to trade a pound of wheat for a pound of fruit. Aside from the obvious issue of fair trade, barter has other problems such timing restraints and quantity restrictions. If you wish to trade wheat for fruit you can only do this if the wheat bananas is needed in the near future (before they rot) or if the fruit is in season or available locally. This is where money as a commodity becomes part of the economic system, where in particular an “IOU” or intermediary resource is needed to counter time delays and quantity restrictions of obtaining a good. This intermediate commodity can then be used to buy goods such as fruit when they are needed. Thus the use of money makes all commodities become more liquid or easier to get hold of – cash is a very liquid form of money today.

When such an intermediary is introduced this becomes the basis of a commodity currency – money backed by a multilateral barter agreement between all participants. Historic origins and examples of such commodity currency include cowry shells in 1200BC China that subsequently developed at the end of the stone age into a system of mock cowry shells made with holes in so they could be threaded into chains. The use of metal coins as commodity currency originates from 500BC where silver was used and was imprinted with various gods and emperors to denote their value. The system of commodity currency in many instances evolved into a system of representative currency. This occurred because banks that came into being to store individual and group wealth, would issue a paper receipt to their depositors, indicating that the receipt was redeemable for whatever precious goods were being stored (usually gold or silver money). These allowed receipts to be traded as money (known as bonds), and for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many currencies were based on representative money through use of the gold standard.

Contemporary western systems of money are traded digitally as numbers on a computer screen, and wealth can be symbolized by the differences in ones and zeros held in an account. Systems of exchange are not succeeded in a linear timeframe as human trade will take whichever mode suits their business objectives, for instance, bartering is still part of the ICT (Information Communication Technology) age, with web technology being utilised to open up a set of complex business models on the basis of barter. It is estimated that the worldwide organized barter exchange and trade industry has grown to an $8 billion a year industry and is used by thousands of businesses and individuals.

This introduction to the development of tools and methods in economics (e.g. barter, gifts, trade, commodity currency, bonds, digital exchange) sets the historical context to the study of how economics can be applied to environmental resources and the built environment with a focus on urban space. The forces that operate to distribute resources and wealth can shape the development of people and place – and this has force has not changed since the origins of human exchange. What is important for this article is to understand how these economic forces have been perceived to influence built and natural environments in the context of a historical shift from rural to urban growth at a global scale. Much of this thinking in western thought has its origins in the enlightenment (or age of reason) period from approximately 1650 to 1800 where an elite movement of intellectuals promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in Church and State. Towards the end of this enlightenment period (18th and 19th Century) and entering a philosophical romanticism period (second half of 18th Century) significant thinkers lived within the industrial revolution and this shaped their writing on how society was adopting to industrial development. Romanticism was calling back to a period of nature as the industry grew, the population rose, and urbanization spread. Whilst any fears of these changes were juxtaposed against industrial benefits such as average incomes rising and population beginning to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth.

- Malthusian Problem

Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) was one writer who took concerns of economic growth and population rise as a consequence of the industrial revolution and extrapolated via thought experiment as to how this population growth would affect social improvement with some respect to environmental (natural) protection (Malthus, 1798).

The Malthusian problem (or similarly phrased Malthusian catastrophe, Malthusian check, Malthusian crisis, Malthusian disaster, Malthusian fallacy, Malthusian nightmare, or Malthusian theory of population) that still resonates in contemporary thinking is the question of whether per capita incomes would inevitably be driven down due to the rise in population levels. This concept is held slightly in check due to the expansion of territories and falling birth rates in more developed countries (such as the US and Western Europe). If applied to more developing countries this line of thinking would argue that poor countries such as those in sub-Saharan Africa remain poor, and its population remain on low incomes, especially as developing countries populations increase and scarce resources become even scarcer.

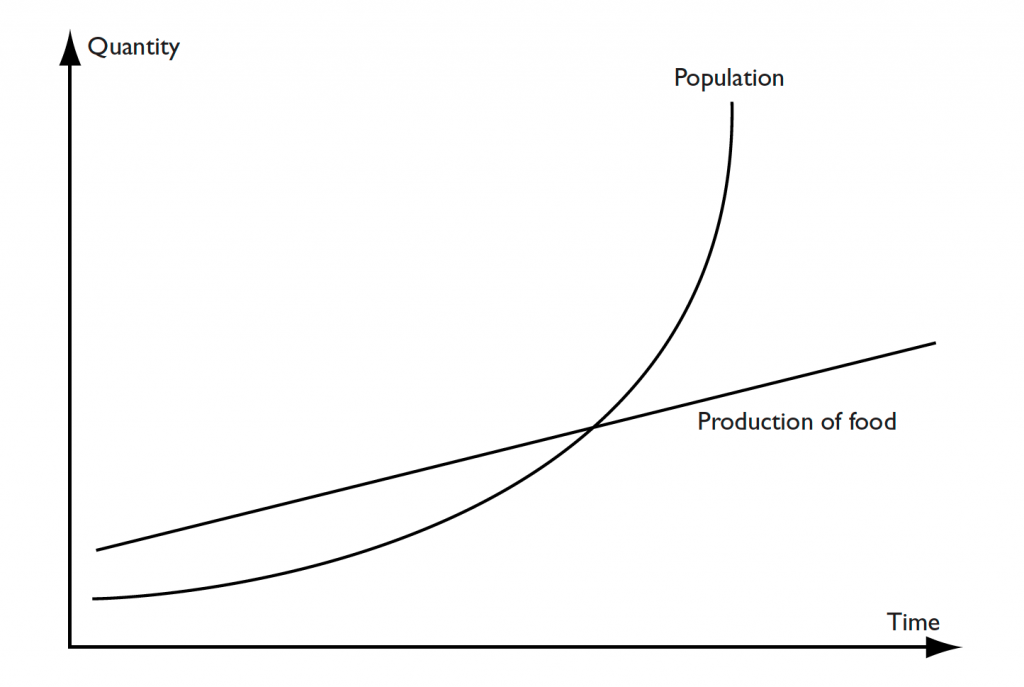

Statistically, it was argued during the time of Malthus’ writing that a nation’s population had a tendency to double itself every 25 years. This meant that mathematically its population grew in a geometric pattern by periodically doubling itself – say from 2 million to 4 million, to 8 million, to 16 million etc. This pattern could be set against a nations food supply that would have to support this population growth. It was argued that food supply growth for consumption increased at a more uniform periodic arithmetic rate as more land was used to produce food – say 2 million tonnes of corn, to 4 million, to 6 million, to 8 million etc. These differences in the reproductive capacity of humans and the reproduction of food available to sustain them were seen to diverge and thus place an ultimate check through food shortage on population growth (Figure 1). Socio-economic impacts of this check were also seen to effect poorer inhabitants of society in urban areas as food becomes scarce. For instance, higher infant mortality in urban areas through lack of nutrition within more disadvantaged groups is recognised when Malthus states that ‘this mortality among the children of the poor has been constantly taken notice of in all towns’ (Malthus, 1798, p.23).

Figure 1: The Malthusian Problem of Population Growth and Food Supply

The simple duality of population growth and food availability is recognised as is the many critiques that can be attached to a more complex issue. For instance, advances in technology may improve the productive capacity of food as seen via developments in fertilizer or pesticides as part of the green revolution. Technological developments or education in birth control may also adjust the dynamics of population increase. This is in addition to wider attitudinal changes such as voluntary restrictions of family size in Western Europe, or more direct regulatory forces such as the one-child policy in China that in principle restricts married, urban couples to having only one child (with exceptions such as ethnic minorities, and parents without any siblings themselves).

- Ricardo

To begin to broaden this economic thinking on environmental resources in urban areas the work by David Ricardo (1772 – 1823) provides an additional dimension of how to trade and the relative price will affect growth. In his book on the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (Ricardo, 1817) further dissection of economic concepts such as rents (and profits, and wages) was applied to theories of land capacity and population. Rents are viewed as the difference between the produce obtained by the employment of two equal quantities of capital and labour. So if land could be used for either cultivation (a price and quantity willing to be paid by a labourer) or for residential purposes (a price and quantity willing to be paid by the household, the rent charged would be the difference in these different land-use options. At the forefront of Ricardo’s thinking was a conclusion that land rent (the reward for owning land) grows as population increases. This would mean that with population growth increasingly concentrating in urban areas consequences would involve a rise in rents of real estate values and a rise in rents of land used for consumption goods. This would generate over a period of time an aggregate appreciation in the value of property and necessity goods such as food.

Ricardo (Ricardo, 1817) also was instrumental in developing the concept of comparative advantage, where at a national scale trade could increase economic growth as long as each nation had different relative costs for producing the same goods. He argued for competitive advantage as all nations could benefit from free trade, even if a nation was less efficient at producing all kinds of goods than its trading partners. This could mean that if a developing nation had an abundance of low-cost materials for manufacturing goods (e.g. Silicon), it could trade on this competitive advantage in order to rebalance its other resources (land, labour, capital, entrepreneurship) that need appropriation or greater efficiency for economic development.

Competitive advantage theory has counter-weight problems in that the type of advantage chosen will form to meet the needs to the rich and powerful and not be a bi-lateral exchange. For instance, the type of competitive advantage chosen such as a nation concentrating on silicon trading may eventually have development gains (and adding value) by manufacturing silicon rather than just natural resource extraction. Although the nation may still be subservient to other nations as during this development shift, wealthier nations will be in a stronger trading position to purchase manufactured silicon parts for a higher added value service sector. This theory is further complicated in that different resources for competitive advantage will be desired during different phases of the development process. For instance, the trading advantages from steel during a global age of heavy manufacturing will be similar to the trading advantages of silicon during a digital revolution. However, the rules of trading and relative prices of commodities will be very different and in greater control of the more developed nations than in previous decades, especially if a greater inequality exists between the developed and developing nations. What is referred to as a Ricardian vice may ring true in that rigorous logic does not always provide a good economic theory and as a result alternative theory must be sought.

- John Stuart Mill

For John Stuart Mill (1806 – 1873) in his book on the principles of political economy (1848) he further developed economic thinking that drew on ideas by Ricardo and the significant neoclassical economic forefather, Adam Smith (Smith, 1776). The book by Mill became a leading economic textbook for 40 years after it was written as it condensed key micro-economic and macro-economic theories whilst contributing more refined and advanced ideas on competitive advantage, economies of scale and opportunity cost. Mill (1848) significantly expressed not just the analysis of changes in population growth (particularly in urban areas) and changes in the productive capacity of necessity and luxury goods. Mill argues that there were limits to such population growth globally, and by extraction, in urban areas because he viewed that growth in the economy and growth in nature were not endless unbounded processes and that they must eventually return to some lasting equilibrium. Linear economic growth was seen due to humanities struggle (especially with respect to western societies) to obtain material advance during the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. In Book IV, Chapter VI, ‘The Stationary State’, Mill takes the view that this material advancement may be to the detriment of ‘real’ wealth in terms of quality of life for individuals and society if the environment is being degraded too severely. With regards to concerns over the environment and quality of life from unlimited economic material gains, he states that:

‘If the earth must lose that great portion of its pleasantness which it owes to things that the unlimited increase of wealth and population would extirpate from it, for the mere purpose of enabling it to support a larger, but not a better or a happier population, I sincerely hope, for the sake of posterity, that they will be content to be stationary, long before necessity compels them to it’ (Mill, 1848)’

This thinking begins to bring in ideas of social welfare as both environmental and social concerns are attached to the economic. For instance, there is thought that well-being, or quality of life, can be maximized when all individuals in society can all consume at the greatest capacity. Well-being is not thought as an ‘average’ or ‘mean’ position where inequalities of wealth distribution could skew the view of well-being for the majority of the population. The movement towards ideas on social drivers (including concerns for the environment as it interacts with the population) became more prominent in the later writings of Mill as he considered the economy in combination with social forces a well as how economics can be thought of as aligned with all things environmental.

Extrapolation of Mills thinking to urban and environmental economics can certainly be drawn. The abolition of inheritance tax and the development of a cooperative wage system were two significant social leanings towards the end of Mill’s writing. For urban areas, this would consider thought as to how a significantly growing number of properties are owned and distributed, plus for an increasingly urbanizing labour force, the distribution of wealth and power appropriated by this class could increase. This was particularly manifest in the rise of union power by those working and living near to labour-intensive manufacturing industries during the industrial revolution.

- Other Significant Authors of Economics and Natural Resources

As Mill opened the way for neoclassical thinking in social progress, Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877 – 1959) brought welfare economic thinking to the fore. As part of the neoclassical writers on welfare economics, Pigou took Alfred Marshall’s (1842 – 1924) Principles of Economics (Marshall, 1890) and concept of externalities by embedded it further into the discipline. Externalities, as are those benefits gained or costs incurred by a third party due to the transactions of buyers and sellers of a good or service. Therefore there can be positive or negative effects on individuals or groups that are external to the market – hence the term externalities. These third-party effects give rise to the notion that a third force (not just producers and consumers) should be able to step in a correct any external benefits or costs. Examples of externalities can link in with urban issues where for instance incidents of health problems by residents near to factories will provide a negative externality cost. This is certainly the case for Chinese cities such as Shanghai where pollution levels (from industry and transport) provide breathing difficulties for residents that may not gain any direct market benefit from the economic activity taking place.

As well as externality examples as urban issues, the development of the built environment can also draw out some cases. For instance, as a simple site-specific example a new build property will have to consider the light that may be taken away from existing residential properties, as in the legal requirement of a ‘right to light’. If the existing residential property does not gain financially from the market transaction of the adjacent new build property but does experience a cost in the amount of light exposure, the residents will be experiencing some degree of a negative externality. A positive externality example could, for instance, be that a resident paints the exterior of his/her house, and therefore raises the aesthetic and economic exchange value of the property, but also raises the third party value of the surrounding neighbourhood and the wider community that benefit from the space in view of the freshly painted house. It should be noted that externality concepts need careful analysis as benefits and costs may be valued differently, for instance in the house painting example, a house painted without care or attention in keeping with what is socially acceptable (e.g. the house could be painted completely black!) could generate a negative rather than positive externality for the wider community.

In order to deal with externalities, Pigou believed that taxes could provide a disincentive to negative externality (or internalise the cost of) problems such as pollution, or that subsidies could provide an incentive to provide (or internalise the cost of providing) positive externalities for the wider society external to the market. The use of taxes or subsidies with regards to dealing with externalities is still referred to in economic circles as Pigovian taxes and subsidies. A fundamental difficulty with this neoclassical approach is the fundamental belief that markets are central – more modern progressive economic thinkers have held that the market may not be central to the analysis of the phenomenon, particularly for the urban and environmental question, as markets can indeed fail.

Market failure is in essence where the market does not efficiently allocate all goods and services. For instance, a large concentration of empty homes lying idle until their eventual decay would appear to be wider inefficient use of resources. We can explore market failure elsewhere, but what is important here with regards to economic thought is that public choice economists such as Ronald Coase in the 1960s would begin to demonstrate that behaviours and actions outside of the invisible hand of the market, and outside of the incentives of tax and subsidy, could affect economic activity. Of particular significance was that integration of legal considerations will affect the decision to carry out a particular economic activity, such as bargaining over land due to legal costs between parties may generate different transaction costs irrespective of what the open market value suggests (Coase, 1960).

Summary

- The origins of economic thinking can be conceived to date back to when humans bartered for goods or exchanged through a system of gifts.

- Money as a commodity becomes part of the economic system, where in particular an “IOU” or intermediary resource is needed to counter time delays and quantity restrictions of obtaining a good

- The system of commodity currency in many instances evolved into a system of representative currency such as gold and through the use of the gold standard.

- Contemporary western systems of money are traded digitally as numbers on a computer screen. Bartering continues to be carried out with an estimated $8 billion a year industry.

- Much of this thinking in western thought has its origins in the enlightenment (or age of reason) period from approximately 1650 to 1800 that promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in Church and State.

- Towards the end of this enlightenment period (18th and 19th Century) and entering a philosophical romanticism period (second half of 18th Century) significant thinkers lived within adaptation to industrial development.

- Romanticism was calling back to a period of nature as industry grew, population rose, and urbanization spread.

- The Malthusian problem is whether per capita incomes would inevitably be driven down due to the rise in population levels. Critiques of this hypothesis is that (1) advances in technology may improve the productive capacity of food; (2) Technological developments or education in birth control may also adjust the dynamics of population increase.; and (3) Wider attitudinal changes such as voluntary or regulatory restrictions of family size.

- Ricardo’s thinking was a conclusion that land rent (the reward for owning land) grows as population increases. This would generate over a period of time an aggregate appreciation in the value of property and necessity goods such as food.

- David Ricardo also was instrumental in developing the concept of comparative advantage. This theory has counter-weight problems in that the type of advantage chosen will form to meet the needs to the rich and powerful and not be a bi-lateral exchange. This is, further complicated in that different resources for competitive advantage will be desired during different phases of the development process

- John Stuart Mill expressed that there were limits to such population growth globally, and he begins to bring in ideas of social welfare .

- In welfare economics Pigou (1877 – 1959) took Alfred Marshall’s (1842 – 1924) Principles of Economics (Marshall, 1890) and the concept of externalities by embedded it further into the discipline. In order to deal with externalities, taxes and subsidies could provide incentives to negative and positive externalities

- Ronald Coase in the 1960s demonstrates that behaviours and actions outside of the invisible hand of the market, and outside of the incentives of tax and subsidy, could affect economic activity.

A full and formated of this post can be cited as:

Squires, G. (2013). Chapter 3 ‘The Built and Natural Environment According to Economists’ in Squires, G. (2013). Urban and Environmental Economics. Routledge.