[3500 Words; 20 Minute Read] It is important to improve understanding of how cities can be better financed to meet affordable housing challenges over the short and long-term; be they economic, social and/or environmental. The lack of adequate affordable housing is a major challenge in the development of human settlements. With rapid urbanization, governments are increasingly having difficulties to meet the growing demand for affordable housing. The lack of revenues is one of the biggest problems facing most cities administrations all over the world, which makes them one of the vulnerable layers of government, with increasing responsibilities and a small share in the allocation of affordable housing. This research project critically analyses the financing of cities by looking at San Francisco City and Bay Area examples of city finance that engage with real estate development of affordable housing. This research is needed to improve the way finance in urban spaces can maintain quality affordable housing in economically constrained circumstances. In turn, this research into the financing of affordable housing in cities facilitates a greater quality of urban places and provides a more sustainable and resilient economic platform with which urban areas can thrive.

This post critically analyses the financing of affordable housing development using the case study of San Francisco and the Bay Area in the United States. Further, it aims to help understand the way finance in urban spaces can maintain quality resources in economically constrained circumstances. The study is set within an era of austerity for city administrations, which provides challenges for all stakeholders whether locally, nationally, or internationally. Lessons to be learnt from the case study are of relevance and importance given the difficult affordable housing issues being faced. The key and important focus of the post is to put forward an improved understanding of how affordable housing development finance challenges can be met.

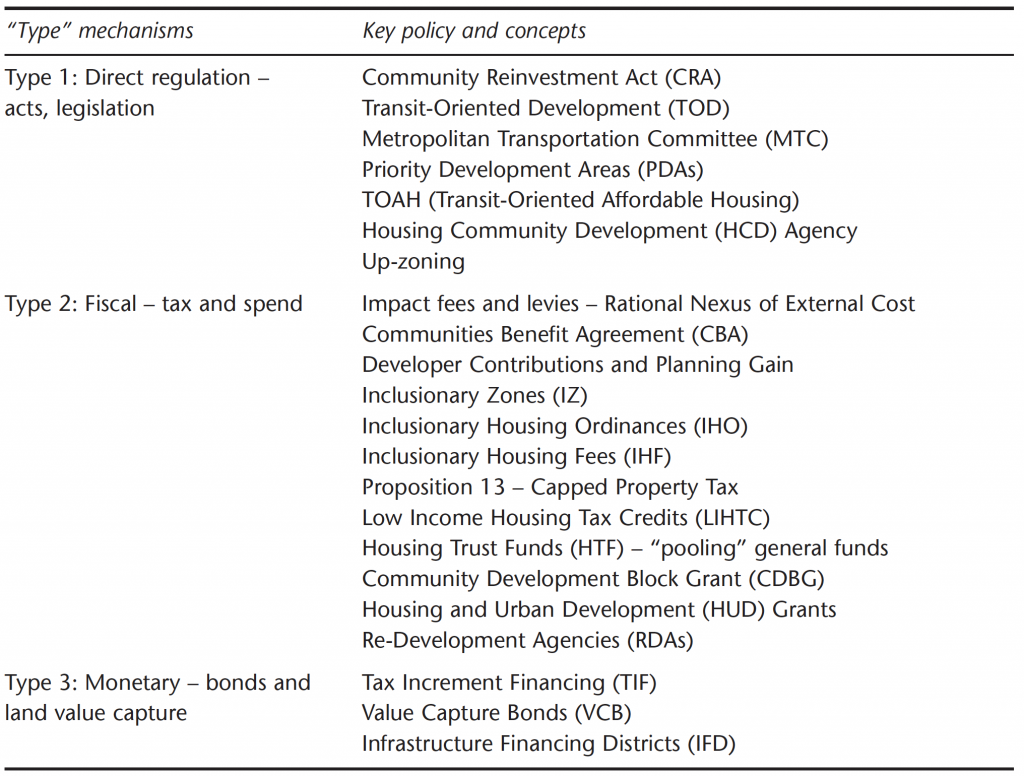

The insight also provides several opportunities: the opportunity for improved management of real estate and financial resources in housing; to provide more value for money for all stakeholders; and subsequently the possibility of creating a better social and environmental condition. Furthermore, it helps to support those who are seeking to find sustainable solutions to the needs and wants of rapidly urbanizing cities, and in some cases de-urbanizing, given increasingly scarce resources – particularly in scarce affordable housing supply. Findings and analysis consider the more technocratic discovery of which specific mechanisms used to finance housing development in cities are most prominent. Different “types” of mechanisms are put forward in the shaping of affordable housing development markets – with “types” being broadly direct, fiscal, and monetary. These “type” mechanisms cover a multitude of acts, bonds, investment trusts, fees and levies, agreements, zone and districts taxes and credits, regulation, recapitalization, and trust funds.

Context of mechanisms in financing affordable housing development

Mechanisms of finance in affordable housing development need to be placed in the context of the case study, although many of the mechanisms’ fundamental principles can provide insights for other places. The aspects of discussion (such as types, weights, and blends) can be considered more conceptually for this case and further cases elsewhere. First of all, the occupation–rent ratio is important when considering the finance for affordable housing development in the case. What is interesting about San Francisco is that it is comprised of 70 percent renters. It is different from the rest of the Bay Area cities, with a composition where the city of San Francisco is polarized largely with extremes of wealthy owners and poor renters (or homeless). Moreover, those in the middle are predominantly renters rather than owner-occupiers.

There is a significant number of non-profits for affordable units in cities of the Bay Area region. The Bay Area has very strong non-profits that have been in business 35–40 years, with cash of USD 20–30 million on their balance sheet. They have become so strong because public policy has driven projects towards affordable housing. In the 1960s and 1970s, the federal government under the direct provision of public housing development mainly provided affordable housing. More recently, affordable housing development has transitioned more towards private enterprise, where non-profits provide the local jurisdictions with an alignment of public policy along with a mission. Despite affordable housing development “enterprise,” the sector still interlinks with more direct provision of funds for affordable provision, albeit in a more sophisticated way to encourage mixed and cohesive communities, such as via the San Francisco (SF) Hope VI and National Hope VI projects. Housing authorities are still heavily involved, and they still are government entities with federal organizations such as Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

“Type” mechanisms for financing affordable housing development

Given these broader contextual considerations in the case study and beyond, the specific mechanisms that channel finance are now put forward. They are conceptualized as “type” layers that work simultaneously, with incentives and selection finance being taken from different types. Here we consider type 1 as direct regulation such as shaping by acts and legislation; type 2 as the fiscal incentives of taxation and spending; and type 3 as monetary effect such as the influence of bonds and land value capture. These three types are seen as fundamental additions to conventional private financing in order to make the development of affordable housing supply “affordable.” Private financing could be, for instance, in the form of institutional funds, loans, trusts, and donations. These three types (see Table 1) are now unpacked to get a great handle on what could be used as a mechanism in the financing of affordable housing development.

Table 1: Affordable housing finance “type” mechanisms

Type 1: Direct regulation – acts, legislation

With regard to the more technical mechanisms at play in affordable housing development in the Bay Area, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) is a fundamental underlying legal instrument that directs the sector. The bulk of multi-family or apartment construction, whether it is new or renovation in the affordable housing sector, is done primarily to satisfy a federal regulatory requirement called the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). CRA is a banking regulation passed in the 1970s at the federal level to prevent red-lining, where low-income neighborhoods are disadvantaged by being labeled so, and thus not invested in. The CRA means that banks are incentivized to reinvest back into the communities that they make their deposits to. Cross-sectoral appeal for affordable housing development finance is particularly found within incentives provided by transport and regional planning. Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) dollars are available through the Metropolitan Transportation Committee (MTC) as a regional planning body. TOD will often involve a sustainable community strategy that has the goal of reducing vehicle miles travelled and of getting the cars off the road in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. TOD is planned to concentrate more development in areas that either have transit stations, or are along transit corridors or transportation corridors. To do so, cities were invited to identify in their general Bay Area plans Priority Development Areas (PDAs), which are pre-identified zones where city plans and permits would encourage development.

To explore PDAs (Priority Development Areas) further, there is resistance among voters to agree development in their own locality. This is largely due to NIMBYism (Not In My Back Yard) behavior, but also due to a lack ofsurrounding infrastructure and fear of further congestion. The business community also has reservations, as the priority areas will not immediately be where economic growth is actually going to happen. Even more so, there is an attitude that it is unlikely to achieve the desired greenhouse gas reductions as an aggregate. Further issues are that the majority of construction is for 1–2 bedroom apartments that are not the preferred choice for most families. This means that the plans may or may not actually have much influence on where people choose to live. Despite this, as congestion gets worse, more people may have the incentive to trade off commuting for family space, and be forced to take up demand for TOD accommodation. The theory is that people will pay a higher value (a premium) to rent a unit or buy a unit within walking distance of transit.

An affordable housing requirement of TOD often involves value capture concepts. Value capture in TOD is based on assessing properties to capture some of its value and pay for the initial transit outlay. In doing so, the large funds generated are used to pay for only Transit- Oriented Development in affordable housing. This type of affordable housing requires a minimum density, depending on where the development is. It also tries to increase densities and obtain a minimum percentage of affordable housing. Most projects are mixing current market rate and affordable housing. The policy here is the affordable housing development financing model known as the TOAH (Transit Oriented Affordable Housing) fund, which is a regional model directed by the State of California’s Housing Community Development (HCD) Agency.

Changes in regulation can generate economic circumstances to strengthen the financial viability of affordable housing development. As well as horizontal zoning, regulatory circumstances can be provided to change viability vertically and in design. Under regulation, local governments have responsibilities to shape the design of buildings, the uses of buildings within certain areas, and the design in terms of height and bulk, and the impact on the street for example. Vertical regulatory changes are referred to as “upzoning” and the development process can “up-zone” a building or a lot to create a greater developable parcel. City administrations can up-zone or down-zone, and that affects whether a developer may come to a community to build on a particular site. This regulatory process is also connected to economic factors such as a strong demand for real estate, both for office and residential. Obviously, larger buildings are more profitable than smaller buildings if there are more units per lot area, even though they may incur higher unit costs. Interestingly, some city administrations have facilitated the up-zoning of many districts in exchange for exacted inclusionary housing units.

Type 2: Fiscal – tax and spend

City administrations can adopt exactions that operate as a subsidy paid by the developer to an administration. These could be, for example, impact fees or inclusionary fees. Inclusionary fees often apply to all new development in a particular land-use category at a uniform rate. These inclusionary fees are charged once for operating costs, but largely for capital costs. In turn, this fee is meant to offset the costs a city administration will incur to build, for instance, a road by using a project’s funds. To incur a fee there has to be a direct connection between the project and the external cost, often referred to as having a “rational nexus.” Impact fees are also similar to exaction although impact fees are like sewer fees or transit fees that go to cover “the impact” of additional density or use in a particular community. Affordable housing could also be part of the impact on a building-by building basis, so there can be an attempt to exact some of the capital for this sector.

The Communities Benefit Agreement (CBA) is used in California and the Bay Area for exaction of fees and levies, and it often exists in specific zones. Within these agreements there is often tension, particularly as developers are struggling with how to deliver the housing, mainly as there are not enough subsidies to make the housing work if the lower affordable housing rents, as part of the agreement, are included in the viability model. Exactions as fees are often referred to as “in lieu fees” connecting to developer contributions as planning gain. Using San Jose in the Bay Area as an example, it demonstrates the issue of external demand and costs on public goods and services that can be extracted from real estate development, particularly if there is a direct rational nexus. San Jose mushroomed in its building of commercial property in the heart of the booming Silicon Valley. As a consequence of this boom, traffic has increased and generated congestion that in turn will need to be dealt with to address concerns over the environment and economic efficiency.

To implement exaction fees and levies in the housing sector of real estate development, Inclusionary Zones (IZ) have been set up to deal with the affordable housing problem. In these zones more specifically the fees are referred to as Inclusionary Housing Ordinances (IHO). Many jurisdictions around the Bay Area have IHOs that require market rate developers to put the new below market rate units on site within their development. Alternatively, the developer has to pay into a fund that is then leveraged to build affordable housing. Furthermore, developers can build affordable units off site but within approximately a mile of the principal permitted project. In essence, the inclusionary zoning process indicates that the developer pays a fee, to either provide onsite units or provide offsite units. Alternatively, in certain locations there may be the option to provide affordable housing development in exchange for permission to build at a slightly higher density than otherwise. So the IZ – in contrast to collections of housing units – are regulatory in nature with an exaction (e.g. a fee) for public benefit in exchange for providing developers with a private benefit.

Inclusionary Housing Fees (IHF) relate more to housing units, rather than the zone, and the fee or levy that is attached to the housing units developed. For example, the city administration can use these fees to generate a “pool” of finance. A developer could be building 100 units at the market rate, but needs to provide a certain percentage (a formula is used to calculate the percentage) within the development that is affordable. Alternatively, the developer can pay a fee – known as an inclusionary housing fee. This fee rarely gets waived because it is a very targeted approach to solving affordable housing. Note that the IHF is on top of impacts to the infrastructure, which generate a separate levy. To note the significance of the IHFs within San Francisco, developers cannot build market rate apartments without having inclusionary housing requirements. Developers either have to set aside units within their development, or developers have to pay a fee or work with a non-profit developer and build affordable housing off site.

Another key fiscal financing mechanism of affordable housing development for the Bay Area and California state-wide is through Proposition 13 (or Prop 13). Prop 13 is a law from 1978 that limits and caps the amount of property tax collected on a homeowner to 1 percent of the value of the house at the time of sale. The property tax bill only increases 2 percent a year until the property is sold again. This cap keeps the tax bill low relative to the appreciation value of the house, plus the city does not see the revenue until the house sells. Furthermore, at the outset, taxes raised by local governments for a designated or special purpose via Prop 13 need to be approved by two-thirds of the voters. As a result of Prop 13, all housing is seen as a loser to most cities, because the administration cannot collect a lot of property taxes to pay for public goods and services – as collection is at the point of sale. Furthermore, the inequities in housing values mean that proportionally the 1 percent capped tax rate is not progressive and cannot extract higher value amounts in tax on higher rate properties and cannot capitalize on rising property prices. As such, local governments are extremely restricted in terms of their ability to generate tax revenue because of Prop 13.

With affordable housing development, Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) are the primary fiscal financing vehicle that allows affordable housing to be built, and allow some modicum of return for the bank. There is a purchasing of tax credits by banks for distribution to a project, and there is also a lending against credits as a form of equity. The LIHTC industry started in 1986 when the tax credits were formally codified within the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) regulations. All the major banks participate in this industry, although it is a specialized field because the process involves dealing with government regulations and IRS and tax implications. In the 1990s when it first started there were a lot of economic investors, because it enabled a dollar for dollar write-off of a company’s tax liability. Today, the market is heavily dominated, not by industry economic investors, but by financial institutions that want an economic return and also want CRA benefits. The credits have a lifespan, similar to a bond, due to the agreement that the affordability has to last for 20 years. Each state is also allowed to have a state credit to add onto the federal tax credits, and federal credits are offered for up to 60 percent of average median income.

A critical point with respect to LIHTCs was that they have a limited lifespan (say 20 years) and do not run in perpetuity. Affordable properties are granted a lifespan as designated affordable, but this means that there is a problem into perpetuity. The affordable housing industry is now doing approved development work that is largely recapitalizing existing affordable developments as they come to the end of their LIHTC life. Developments could be in tax credit developments that were undertaken 15 or 20 years ago, and that are coming to the end of their initial compliance period, or are even older developments. The problem is if all of those resources are going towards redevelopment of older tax credit developments, the industry is not supporting new affordable housing. Furthermore, the tax credit program has a difficulty in that it does not work well for buying existing market value apartments. Essentially from the start of the LIHTC project there is approximately a year until all of units have to be occupied, meaning there is no strict mechanism to phase in the credit.

Of the city funds available, an emerging fiscal mechanism of funding for affordable housing development is via Housing Trust Funds (HTF) that are administered by a city government. The HTF is a general fund set aside for the purposes of supporting affordable housing development, and is valued at USD 1.5 billion over a 30-year period. Local HTFs collect dollars in different ways. Sometimes cities are putting their own federal HUD money into the fund, as well as their own Community Development Block Grant money from HUD. Sometimes cities also charge a transfer tax on each market rate sale (e.g. Prop 13) that can go into a housing fund pot. Berkeley is one city that does this independent of redevelopment agencies, as was carried out in the previous system prior to the Re-Development Agencies (RDAs) being dismantled. San Francisco city administration has got a housing trust fund set up and approved by voters (via Proposition C). This means that city authorities can capitalize finance themselves and have a setaside property tax fund. The San Francisco city and county HTF is used for people on moderate incomes, such as police and fire fighters. The focus will be to replace some 3,000 public housing units that need rehabilitating, particularly those that house people living in extreme poverty.

Type 3: Monetary – bonds and land value capture

Government-backed lending of money can be considered a monetary type of finance mechanism that can stimulate affordable housing development. The raising of finance via lending to project districts on the basis of future clawback in taxes is the basis of tax increment financing (TIF). TIF money in the Bay Area was instrumental in gaining match-funding grants from the federal renewal program – with TIF enabling affordable housing development via the redevelopment agency. The termination of RDAs in California on January 2012 effectively ended state-wide TIF being used as a major funding mechanism for dealing with local “blight” in the real estate (re)development process. Commentators noted the underlying reason for RDA abandonment being due to the large budget shortfall and in order to protect funding for core public services at the local level. The RDAs (funded largely by TIF) played a significant role in San Francisco and their loss will be felt in the remediation of “blight,” although investment at the high end of the housing development market will no doubt continue.

Given the demise of TIF bonds to deal with blight, other mechanisms have been introduced or are being made more use of to enable leverage of finance against future uplift of taxes – namely the use of Value Capture Bonds (VCB) in Infrastructure Financing Districts (IFD) without a necessity to focus on blight and hence redevelopment. These have already been available for a long time in California, and it is a diversion of existing property tax (see Prop 13) to a special financing district. The IFDs have a limited set of purposes that are allowed, and there is a requirement for a certain percentage of the property owners affected to approve development. This generates some difficulties for city administrations, as there are always multiple property owners. As a special case to highlight these districts, the Port Authority in San Francisco have their own IFD, as they control all of their own property. As a result, they create ground leases and control a large amount of San Francisco’s waterfront, with which special legislation helped create their own IFD. This means that the Port Authority does not need to get property owner votes, because they are the property owner. As such, the use of IFDs to finance affordable housing development is weak, as the priority will be to pay off initial bonds related to infrastructure rather than incentivizing less than market rate housing.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this discussion has argued that mechanisms for financing affordable housing development are indeed important and have varying degrees of power and influence. The case study can draw out many mechanisms set within the context of high ratios of renters in booming cities, a leading and high volume of mission-based, not-for-profit affordable housing developers, and an increasingly enterprising approach that was formally a large remit of direct provision. It was found that the most significant mechanisms could be considered as direct, fiscal, or monetary “types” in shaping affordable housing at less than market rate. For instance, the Credit Reinvestment Act as a direct mechanism, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program as a fiscal mechanism and Value Capture Bonds as a monetary mechanism, are ways in which sense can start to be made of the plethora of mechanisms on offer. Thinking of such types as acting within the development “process” by affordable housing developers further crystallizes understanding.

A full and formatted version of the post can be cited as: Squires, G. (2018). ‘Mechanisms for Financing Affordable Housing Development’ in Squires, G., Heurkens, E., Peiser, R., (2018). Companion to Real Estate Development. Routledge.