It can be seen that classical economic thought on property and planning is relatively young with writers dating back to the 18th century.

This is not to suggest that settlements did not have pressing social and environmental considerations prior to their intellectual conception. For instance, problems of sanitation, pollution, and availability of resources in urbanising towns are documented prior to the formalisation of intellectual debate.

Furthermore, there would have been interest groups as institutions beyond scholarly writers that articulated property and planning difficulties that would need to be overcome in order to further their own individual and collective interests.

For instance, political parties, informal pressure groups, social movements, land and property owners, and merchants held property and planning interests. In the more recent past, groups of both scholars and wider interest groups as institutions have begun to propel property concerns and planning-based problems that face humanity.

For Institutional Economics, the work of Veblen on the theory of the leisure class (1899) began to lead the way on institutionalist thinking in economics. The idea is that economics can be dynamic rather than static, given the fluidity of institutional power and change.

A further core writer on institutional economics is Galbraith and his work on ‘The Affluent Society’ (1958). Here, we see a demonstration of the growing significance of wealth in the private sector relative to the public sector, so having significant institutional economic power to affect economic outcomes.

Moving more into ‘new’ institutional economics are public choice economists such as Ronald Coase in the 1960s. Coase would begin to demonstrate that behaviours and actions outside of the invisible hand of the market and outside of the incentives of tax and subsidy could affect economic activity.

Of particular significance was that integration of legal considerations will affect the decision to carry out a particular economic activity, such as bargaining over land due to legal costs between parties may generate different transaction costs irrespective of what the open market value suggests (Coase, 1960).

In the new institutional economic subdiscipline, Williamson demonstrates that the internal economics of organisations are important to the outcomes of markets and associated hierarchies (1975).

In terms of governance and policy, Ostrom’s work on ‘Governing the commons’ (1990) more normatively stresses that the commons are less of a tragedy and more a point of collective call to action, if institutions and their evolution are put upfront in the economic analysis.

As such, the work challenges the notion that common property will fail due to monopolistic tendencies. Eggertsson (2005) raises further institutionalist thought that institutions themselves are imperfect with some possibilities and limitations for reform.

The strength and depth of this field can be seen in Furubotn et al.’s (2005, 2nd edition) text on the contribution of NIE to economic theory.

Institutions can also be seen in economic application to economic geography and property. The work by Storper (2013) in ‘Keys to the city’ demonstrates an economic geography take on how economics, institutions, social interaction, and politics shape development.

Ball (2016) applies markets and institutions to the field of real estate and construction. Whilst Squires and Heurkens (2015) provide institutional examples of international approaches to real estate development.

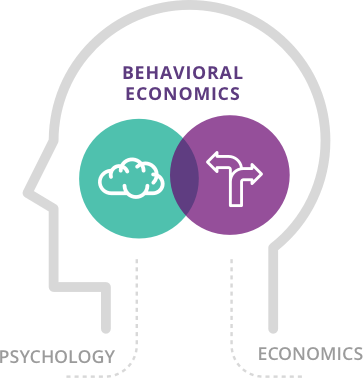

Behavioural economics work also has taken the economics field into more heterodox directions and thus new directions and implications for property and planning.

Shiller’s (2000) work on irrational exuberance has argued early on that markets are driven by psychological and social factors rather than fundamental values, especially in later editions that consider housing market bubbles.

Thaler and Ganser (2015) in ‘Misbehaving’ gather behavioural examples in a popular format. Plus Kahneman (2011) in the popular economic-psychology book ‘Thinking, fast and slow’ takes economics into psychology territory, largely by distinguishing between instinct and thought in making economic decisions.

Economic decision-making both individually and collectively is certainly a core aspect of property and planning, and this consideration to the field of institutional economics and behavioural economics is paramount.