[2000 Words; 10 Minute Read] It is important to improve understanding of how cities can be better financed to meet affordable housing challenges over the short and long-term; be they economic, social and/or environmental. The lack of adequate affordable housing is a major challenge in the development of human settlements. With rapid urbanization, governments are increasingly having difficulties to meet the growing demand for affordable housing. The lack of revenues is one of the biggest problems facing most cities administrations all over the world, which makes them one of the vulnerable layers of government, with increasing responsibilities and a small share in the allocation of affordable housing.

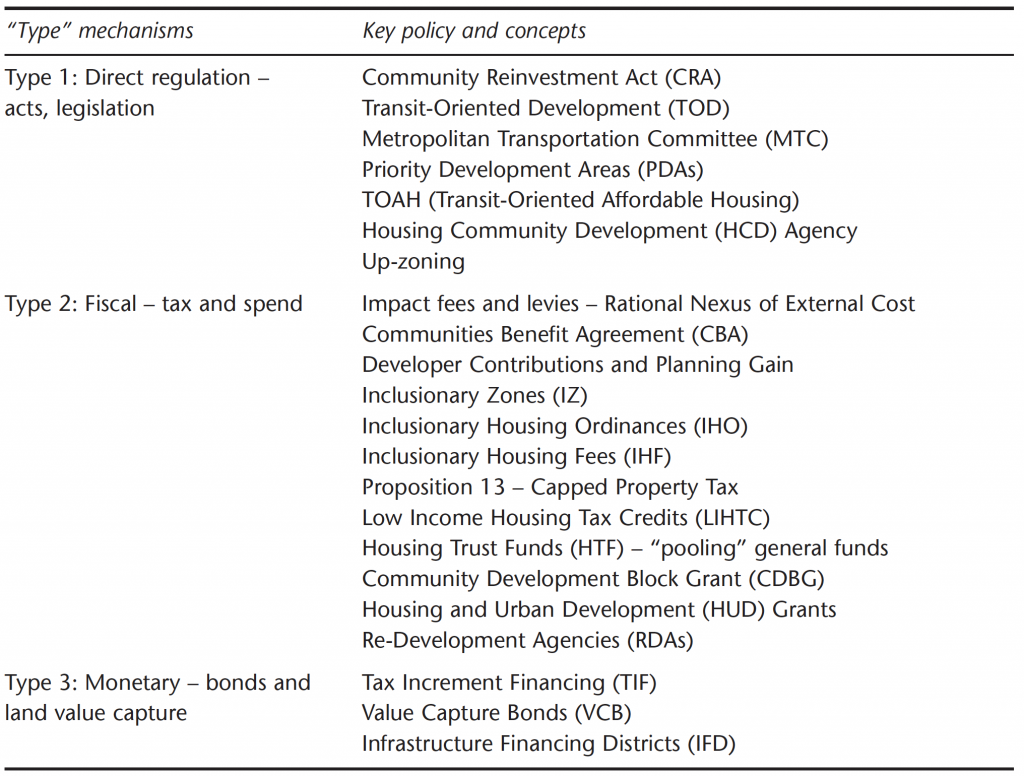

“Type” mechanisms for financing affordable housing development

The specific mechanisms that channel finance can be conceptualized as “type” layers that work simultaneously, with incentives and selection finance being taken from different types. Here we consider type 1 as direct regulation such as shaping by acts and legislation; type 2 as the fiscal incentives of taxation and spending; and type 3 as the monetary effects such as the influence of bonds. These three types are seen as fundamental additions to conventional private financing in order to make the development of affordable housing supply “affordable.” Private financing could be, for instance, in the form of institutional funds, loans, trusts, and donations. The ‘Type 2 Fiscal’ mechaisms (see Table 1) are now unpacked to get a great handle on what could be used as a mechanism in the financing of affordable housing development.

Table 1: Affordable housing finance “type” mechanisms

Type 2: Fiscal – tax and spend

City administrations can adopt exactions that operate as a subsidy paid by the developer to an administration. These could be, for example, impact fees or inclusionary fees. Inclusionary fees often apply to all new development in a particular land-use category at a uniform rate. These inclusionary fees are charged once for operating costs, but largely for capital costs. In turn, this fee is meant to offset the costs a city administration will incur to build, for instance, a road by using a project’s funds. To incur a fee there has to be a direct connection between the project and the external cost, often referred to as having a “rational nexus.” Impact fees are also similar to exaction although impact fees are like sewer fees or transit fees that go to cover “the impact” of additional density or use in a particular community. Affordable housing could also be part of the impact on a building-by building basis, so there can be an attempt to exact some of the capital for this sector.

The Communities Benefit Agreement (CBA) in the United States is used for exaction of fees and levies, and it often exists in specific zones. Within these agreements there is often tension, particularly as developers are struggling with how to deliver the housing, mainly as there are not enough subsidies to make the housing work if the lower affordable housing rents, as part of the agreement, are included in the viability model. Exactions as fees are often referred to as “in lieu fees” connecting to developer contributions as planning gain. This approach demonstrates the issue of external demand and costs on public goods and services that can be extracted from real estate development, particularly if there is a direct rational nexus.

To implement exaction fees and levies in the housing sector of real estate development, Inclusionary Zones (IZ) have been set up to deal with the affordable housing problem. In these zones more specifically the fees are referred to as Inclusionary Housing Ordinances (IHO). Many jurisdictions in the United States have IHOs that require market-rate developers to put the new below market-rate units on-site within their development. Alternatively, the developer has to pay into a fund that is then leveraged to build affordable housing. Furthermore, developers can build affordable units off site but within approximately a mile of the principal permitted project. In essence, the inclusionary zoning process indicates that the developer pays a fee, to either provide onsite units or provide offsite units. Alternatively, in certain locations there may be the option to provide affordable housing development in exchange for permission to build at a slightly higher density than otherwise. So the IZ – in contrast to collections of housing units – are regulatory in nature with an exaction (e.g. a fee) for public benefit in exchange for providing developers with a private benefit.

Inclusionary Housing Fees (IHF) relate more to housing units, rather than the zone, and the fee or levy that is attached to the housing units developed. For example, the city administration can use these fees to generate a “pool” of finance. A developer could be building 100 units at the market rate, but needs to provide a certain percentage (a formula is used to calculate the percentage) within the development that is affordable. Alternatively, the developer can pay a fee – known as an inclusionary housing fee. This fee rarely gets waived because it is a very targeted approach to solving affordable housing. Note that the IHF is on top of impacts on the infrastructure, which generate a separate levy. To note the significance of the IHFs, developers cannot build market-rate apartments without having inclusionary housing requirements. Developers either have to set aside units within their development, or developers have to pay a fee or work with a non-profit developer and build affordable housing off site.

Another key fiscal financing mechanism of affordable housing development is at State level. For California, mechanisms are through Proposition 13 (or Prop 13). Prop 13 is a law from 1978 that limits and caps the amount of property tax collected on a homeowner to 1 percent of the value of the house at the time of sale. The property tax bill only increases 2 percent a year until the property is sold again. This cap keeps the tax bill low relative to the appreciation value of the house, plus the city does not see the revenue until the house sells. Furthermore, at the outset, taxes raised by local governments for a designated or special purpose via Prop 13 need to be approved by two-thirds of the voters. As a result of Prop 13, all housing is seen as a loser to most cities, because the administration cannot collect a lot of property taxes to pay for public goods and services – as collection is at the point of sale. Furthermore, the inequities in housing values mean that proportionally the 1 percent capped tax rate is not progressive and cannot extract higher value amounts in tax on higher rate properties and cannot capitalize on rising property prices. As such, local governments are extremely restricted in terms of their ability to generate tax revenue because of Prop 13.

With affordable housing development, Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) are the primary fiscal financing vehicle that allows affordable housing to be built, and allow some modicum of return for the bank. There is a purchasing of tax credits by banks for distribution to a project, and there is also a lending against credits as a form of equity. The LIHTC industry started in 1986 when the tax credits were formally codified within the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) regulations. All the major banks participate in this industry, although it is a specialized field because the process involves dealing with government regulations and IRS and tax implications. In the 1990s when it first started there were a lot of economic investors, because it enabled a dollar for dollar write-off of a company’s tax liability. Today, the market is heavily dominated, not by industry economic investors, but by financial institutions that want an economic return and also want CRA benefits. The credits have a lifespan, similar to a bond, due to the agreement that the affordability has to last for 20 years. Each state is also allowed to have a state credit to add onto the federal tax credits, and federal credits are offered for up to 60 percent of average median income.

A critical point with respect to LIHTCs was that they have a limited lifespan (say 20 years) and do not run in perpetuity. Affordable properties are granted a lifespan as designated affordable, but this means that there is a problem into perpetuity. The affordable housing industry is now doing approved development work that is largely recapitalizing existing affordable developments as they come to the end of their LIHTC life. Developments could be in tax credit developments that were undertaken 15 or 20 years ago, and that are coming to the end of their initial compliance period, or are even older developments. The problem is if all of those resources are going towards redevelopment of older tax credit developments, the industry is not supporting new affordable housing. Furthermore, the tax credit program has a difficulty in that it does not work well for buying existing market value apartments. Essentially from the start of the LIHTC project there is approximately a year until all of units have to be occupied, meaning there is no strict mechanism to phase in the credit.

Of the city funds available, an emerging fiscal mechanism of funding for affordable housing development is via Housing Trust Funds (HTF) that are administered by a city government. The HTF is a general fund set aside for the purposes of supporting affordable housing development and is valued at USD 1.5 billion over a 30-year period. Local HTFs collect dollars in different ways. Sometimes cities are putting their own federal HUD money into the fund, as well as their own Community Development Block Grant money from HUD. Sometimes cities also charge a transfer tax on each market-rate sale (e.g. Prop 13) that can go into a housing fund pot. Berkeley is one city that does this independent of redevelopment agencies, as was carried out in the previous system prior to the Re-Development Agencies (RDAs) being dismantled. San Francisco city administration has got a housing trust fund set up and approved by voters (via Proposition C). This means that city authorities can capitalize finance themselves and have a setaside property tax fund. As an example for San Francisco city and county, HTF is used for people on moderate incomes, such as police and firefighters. The focus will be to replace some 3,000 public housing units that need rehabilitating, particularly those that house people living in extreme poverty.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this discussion has argued that mechanisms for financing affordable housing development are indeed important and have varying degrees of power and influence. It was found that the most significant mechanisms could be considered as direct, fiscal, or monetary “types” in shaping affordable housing at less than market rate. For instance, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program as a fiscal mechanism, is a way in which sense can start to be made of the plethora of mechanisms on offer in the United States.

A full and formatted version of the post can be cited as: Squires, G. (2018). ‘Mechanisms for Financing Affordable Housing Development’ in Squires, G., Heurkens, E., Peiser, R., (2018). Companion to Real Estate Development. Routledge.