Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) was one writer who took concerns of economic growth and population rise as a consequence of the industrial revolution and extrapolated via thought experiment as to how this population growth would affect social improvement with some respect to environmental (natural) protection (Malthus, 1798).

The Malthusian problem (or similarly phrased Malthusian catastrophe, Malthusian check, Malthusian crisis, Malthusian disaster, Malthusian fallacy, Malthusian nightmare, or Malthusian theory of population) that still resonates in contemporary thinking is the question of whether per capita incomes would inevitably be driven down due to the rise in population levels. This concept is held slightly in check due to the expansion of territories and falling birth rates in more developed countries (such as the US and Western Europe). If applied to more developing countries this line of thinking would argue that poor countries such as those in sub-Saharan Africa remain poor, and its population remain on low incomes, especially as developing countries populations increase and scarce resources become even scarcer.

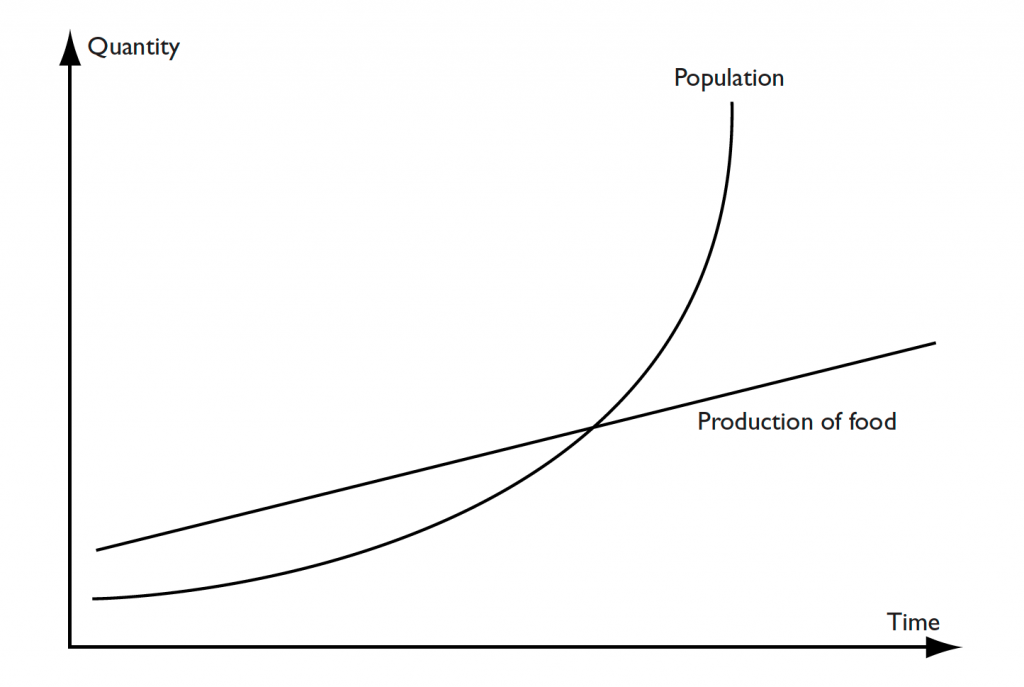

Statistically, it was argued during the time of Malthus’ writing that a nation’s population had a tendency to double itself every 25 years. This meant that mathematically its population grew in a geometric pattern by periodically doubling itself – say from 2 million to 4 million, to 8 million, to 16 million etc. This pattern could be set against a nations food supply that would have to support this population growth. It was argued that food supply growth for consumption increased at a more uniform periodic arithmetic rate as more land was used to produce food – say 2 million tonnes of corn, to 4 million, to 6 million, to 8 million etc. These differences in the reproductive capacity of humans and the reproduction of food available to sustain them were seen to diverge and thus place an ultimate check through food shortage on population growth (Figure 1). Socio-economic impacts of this check were also seen to effect poorer inhabitants of society in urban areas as food becomes scarce. For instance, higher infant mortality in urban areas through lack of nutrition within more disadvantaged groups is recognised when Malthus states that ‘this mortality among the children of the poor has been constantly taken notice of in all towns’ (Malthus, 1798, p.23).

Figure 1: The Malthusian Problem of Population Growth and Food Supply

The simple duality of population growth and food availability is recognised as is the many critiques that can be attached to a more complex issue. For instance, advances in technology may improve the productive capacity of food as seen via developments in fertilizer or pesticides as part of the green revolution. Technological developments or education in birth control may also adjust the dynamics of population increase. This is in addition to wider attitudinal changes such as voluntary restrictions of family size in Western Europe, or more direct regulatory forces such as the one-child policy in China that in principle restricts married, urban couples to having only one child (with exceptions such as ethnic minorities, and parents without any siblings themselves).

Malthus, T. R. (1798). An Essay on the Principle of Population. Oxford University Press